|

Chapter One Gold. Symbol Au. Atomic number 79. Dictionary definition: "a yellow malleable ductile metallic element." You could say my family is obsessed with it. For my mother's fortieth birthday, my father commissioned a grand piano with 24-karat gold keys. The entire piano is covered in gold leaf and is the tackiest instrument ever played. He tried to smash it with a hammer after she disappeared, but my oldest brother talked him out of it. So he satisfied himself with sealing the double doors of the music room shut. All of which only partially explains why I was stuck on the chandelier in the foyer, dangling upside down and hoping that the chain holding the chandelier wouldn't break. I'd planned to spend this Saturday night out, with the goal of healing my shattered heart. You see, according to our family stories, back in the Dark Ages when we both hunted and were hunted, our ancestors used to console themselves after being thwarted in love by gorging on elk carcasses, telling stirring tales of heroic exploits, and burning all their ex-lovers' belongings -- and occasionally the ex-lover himself. So I'd decided that I'd go back to my roots by eating buttery popcorn, watching an action movie with no romance whatsoever, and then burning old mementos of my ex-boyfriend Ryan on the barbecue grill. Bringing Gabriela (a non-wyvern who sits next to me in Modern Wyvern History class) so I wouldn't be alone -- my old friends ditched me when Ryan did -- I'd bought my ticket and a tub of popcorn, but I couldn't do it. Just couldn't. I'd fled the theater, abandoning Gabriela and the popcorn but taking my mementos -- a Valentine's Day card that played the chicken dance, a strip of photos from a carnival photo booth taken on Santa Monica Pier during a trip to the California Stronghold, and the perfect replica (in miniature) of a talon, cast in gold, on a matching gold chain that Ryan gave me for my birthday only a few weeks before he decided to end years of friendship and several months of enthusiastic kissing. I wore the necklace home, tucked under my shirt, over my stupidly sentimental heart. I was looking forward to moping in an empty house -- you know, sighing loudly, singing off-key to depressing music, and wearing pajamas inside out because you're too sad to reverse them -- without any commentary from any of my brothers. All of them have zero tolerance for a proper sulk, and they're impossible to avoid, even though our house is enormous, with six bedrooms and eight bathrooms. (Don't ask me why so many bathrooms. My brother Liam, one of the twins, claims one of our grandfathers was enamored with the idea of indoor plumbing -- apparently they didn't have it back Home and he was a recent exile. Liam said our illustrious grandfather had even purchased gold bathroom fixtures, then immediately panicked about thieves and hid them. So underneath the floorboards in one of the six bedrooms, there's supposedly a stash of solid-gold toilet handles. I looked for them one summer but no luck. It's possible Liam was lying. He likes to mess with me.) Anyway, I came home, let myself in, kicked off my shoes, reset the locks and perimeter alarms, and then raided the refrigerator for leftover Chinese food. Taking a container of lo mein, I was walking up the back staircase to my bedroom when I heard the faint tinkle of breaking glass from the front of the house. Midstep, I froze. I ran through the possibilities: someone dropped a glass (impossible, since no one was home), a knickknack was precariously perched and fell on its own (possible, since we have a lot of knickknacks), or a thief was breaking in (unlikely, since the alarms hadn't sounded). I was certain it was the middle option, but we've been raised to be paranoid, so I clutched my lo mein and raced the rest of the way upstairs to the security room. My feet were silent on the plush carpet. Stopping in front of the door, I pressed my finger on the ID pad. It didn't unlock. I tried another finger. Still no click of recognition. Beginning to worry, I tried the doorknob, and the door swung open easily. Inside, all the security TVs showed static. The lo mein slipped from my fingers. It hit the floor, and the noodles scattered across the carpet. Lunging forward, I slapped the master alarm. Silence. No red light. No siren. I picked up the phone. Also silence. And there weren't any cell phones in the house. We don't use them. They're too easy to hack and track. I knew exactly what I was supposed to do: get to the safe room, triple-lock the door, and stay there until Dad came home and I heard the all clear. We'd drilled this dozens of times. Over the years, my brothers and I had stashed all our favorite snacks and games in the safe room to entertain us during the longer drills. But this wasn't a drill, and my brothers weren't home. So I did something stupid. Standing in the security room, noodles around my feet, static on the screens . . . I lost my temper. My name is Sky Hawkins. You may have seen my family name in the newspapers or on TV. Wyverns, distantly related to King Atahualpa (who saved the Inca Empire), Sir Francis Drake (a pirate who was knighted by the queen of England), and that guy who started the California Gold Rush and also the guy who stopped it. Billionaires who lost half our fortune in an investment scam. Socialites whose mother went missing in the midst of the scandal. And me, the youngest, the debutante, whose boyfriend publicly dumped her in the wake of the mess, during the last Wyvern Reckoning. It's been a rotten month, and I did not want to add "estate robbed" to the list of things that went wrong. When I lose my temper, I don't explode; I shrink in. The world narrows down to me and whoever or whatever has wronged me. It feels as if time slows, and everything looks bright and sharp. Tunnel vision, my father calls it. My heart beat faster. Adrenaline pumped through my veins. But I felt calm, as if the past and future had fallen away and all that existed was this moment, with me upstairs and the intruder (or intruders) downstairs. Scooping up my chopsticks (because any weapon is better than none), I moved down the hall toward the front staircase. My steps were still silent. The carpet's thick, and my feet were bare. At the top of the grand staircase, I stopped and listened. No footsteps. No voices. No more breaking glass. These stairs could squeak if you didn't know exactly where to step, which I did, thanks to plenty of practice sneaking midnight snacks. Creeping down the curved staircase, I scanned the foyer. Only a few lights were on, spotlights on my father's favorite statues of our more illustrious ancestors. Shadows crisscrossed the tile floor. The windows on either side of the vast front door were intact, and the door was still locked, triple deadbolts. Keeping to the shadows, I slipped across the foyer to the dining room. No intruders. No broken windows. Crossing back, I peeked into the front sitting room -- again, no sign of entry. I then checked the door to the basement, but the lock was untouched. Odd. Very odd. The intruder knew our systems and how to disable them. Given that, he or she most likely knew the layout of the house, as well as which rooms had the most valuables. But the thief hadn't emptied the china cabinet with the gold plates or gone for the wine cellars, which led to the vault, and he hadn't visited any bedrooms for any personal jewels. He'd chosen the front of the house, which had the foyer, the dining room, the front sitting room . . . and the music room. Mom's piano. No way was I letting anyone steal that. Dad always says that executing a heist is like a chess game: you plan for every contingency, and you have backup plans. Stopping a heist, though, is entirely different. You have to improvise. I hate improv. Carefully, quietly, I slipped across the foyer and pressed my eye to the keyhole. At first, all I saw was the piano itself, gleaming in the moonlight. I thought of Mom, practicing Bach, note after note, while my brothers blasted their competing music from their rooms. I liked to sit on the couch by the window, doing my homework, listening to her. . . . A black shadow slipped in front of my view. I drew back. Heart thumping, I forced myself to look again. I needed to know what I was up against. This time, I saw them: three men, dressed all in black, their faces hidden. Two were lifting one side of the piano; the third was shoving a platform with wheels under one of the legs. I ducked down. Three men. One, I could handle. Maybe two, if I were clever enough. Not three. Think, Sky, I told myself. Think fast. The men were lifting the piano onto wheels. That meant they planned to take the entire thing, which meant they couldn't leave via the windows -- much too narrow for a grand piano. They'd have to open the doors that Dad had sealed shut. If I could hold them here, just until someone else came home . . . Spinning around, I scanned the foyer. Statues, vase with flowers, mirrors on wall . . . By the door, there was a pile of mail, plus my brother Tuck's fishing supplies. It was his newest hobby, after his failure at beekeeping. (Seriously, Tuck? Beekeeping?) I beelined for them. No fishing rod, but the box held tackle, copious amounts of fishing line, and a hideous plaid hat. Behind me, I heard a hiss. I turned to see a line of char on the music room door. It spread, inch by inch, top to bottom. Dad had melted the hinges, so the thieves were carving their own way through. Grabbing the fishing hat, I booked it to the door and hung the hat over the knob, so it would block the view through the keyhole, and then I worked fast: taking the fishing line and weaving it between the bases of the statues and the legs of various end tables. Goal was simple: slow the thieves. The line of char now was all the way down one side of the door and proceeding to the right. Blue smokeless flame licked at the ash. It looked like a blowtorch, but I'd bet a wheelbarrow full of gold that these weren't ordinary human thieves and this wasn't any kind of torch. These men were like us. Wyverns, aka were-dragons, aka distant descendants of the (extinct) mighty dragons of old who once dominated the skies of Home. In other words, these men were dangerous. Now would be the time to hide in the safe room. Still, I hesitated. The fishing line might trip them (best case) or slow them (second-best case) for a few minutes, but it wouldn't stop them. If only I could sound an alarm . . . I had a thought, the kind that feels like there's a cartoon lightbulb over your head. All the security alarms were on the same computerized system. But we also had ordinary battery-powered smoke alarms that my father cursed at whenever the batteries

ran out and they started to beep. We had no need for high-tech ones -- we aren't afraid of fire, only theft. There was one on the ceiling of the foyer, next to the chandelier.v

Running up the stairs, I climbed onto the railing. The chandelier was only a few feet from me, close enough to change the lightbulbs. The alarm was a few feet beyond

it. Grabbing one of the golden arms of the chandelier, I stepped on. It swung under my weight. Shifting, I inched closer to the alarm. Now I only had to trigger it. I needed something to set on fire. I reached into my pocket for the chopsticks. You can do this, I told myself. Breathe. Stay calm. Center yourself. I tried to remember the lessons that had been drilled into me: Draw the flame from your center,

think of warmth, believe in the heat. And dream of flying free through the sky in your true form, on your own wings, the sun on your scales, the world beneath your talons. Pursing my lips in an O, I breathed out a tendril of fire. The tiny flame landed on the chopstick and then died. Below, the wood of the door creaked. Block it out, I told myself. Focusing, I breathed, trying to summon more fire. The flame seared up my throat and out my mouth.

It shot onto the chopstick, and the chopstick caught fire. Leaning forward, I stretched out my arm, holding the fiery chopstick so that the smoke rose up toward the sensor. As the ash crumbled, the door began to fall. The men caught it before it crashed. Carrying it back into the music room, they set it aside, leaving a gaping hole. They

began to wheel the piano into the foyer. The first man was walking backward, and his ankles hit the fishing line. He lost his balance and fell, pulling the line with him -- and yanking down the statue of Sir Francis Drake that it was

tied to, which pulled over the end tables. Thief, statue, and tables all crashed down. The vase of flowers shattered, spraying shards of glass across the tile. And the smoke alarm began to wail. My fingers slipped, and I dropped back, hanging from my knees, upside down, from the chandelier. Swearing, two of the men tried to help the one who had fallen as the

front door to the house slammed open. A familiar figure filled the doorway. My father put his hands on his hips. "You are all idiots," he proclaimed. "Give me one good reason why I shouldn't disown you all." Below me, the three thieves snapped to attention. Oh, no, I thought. "Clean up this mess and meet me in my office," Dad said. "And get your sister down from the ceiling. We are not monkeys; we should not act like them." All three of my brothers looked up at me. Dangling upside down by my knees, I waved at them and managed a weak smile.

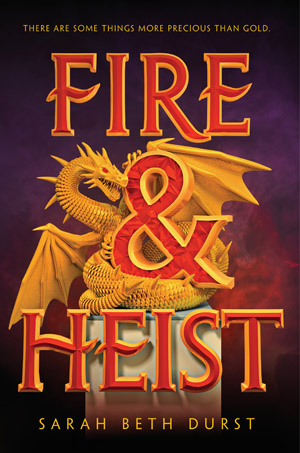

Available now from Penguin Random House / Crown Books for Young Readers. Buy this book from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Books-a-Million, Bookshop.org, or your local independent bookseller. Return to Excerpts page.

ISBN: 9781101931004

|

Excerpt from

Excerpt from